|

|

[http://tlpj.org/left_nav_interior.htm]

|

For a PDF version of this article click here. Judge Takes on Bush on Mountaintop MiningBy FRANCIS X. CLINES

LEWISBURG, W.Va., May 16 - The towering strip mining machines that have been systematically decapitating mountains in Appalachia have once again run up against a flinty federal judge convinced that government agencies illegally allow the coal industry to pollute and obliterate the region's vital waterways with millions of tons of waste. In a direct challenge to the Bush administration, the judge, Chief Judge Charles H. Haden II of the Southern District of West Virginia, found last week that the administration's new rule change that allows the dumping of mining rock and dirt into the streams and valleys of Appalachia is an "obvious perversity" of the Clean Water Act. "The rule change was designed simply for the benefit of the mining industry and its employees," Judge Haden ruled. He ordered the Army Corps of Engineers to stop issuing permits to companies that have been dumping millions of tons of waste into hundreds of miles of waterways and hollows in the mining practice known as mountaintop removal. This is the process of blasting away mountaintop rock to reach low-sulphur coal veins with mammoth bulldozers and drag lines. The practice pours waste down into the mountain hollows, where residents have been increasingly displaced or bought out by the companies. Judge Haden's ruling has stunned the Appalachian coal industry, which warns that the decision could, in theory, shut down any mine in the nation that dumps waste into water. But it has cheered environmental groups that have been contending that the Bush administration, mindful of three critical electoral votes Republicans won here in the close 2000 presidential election, has rewarded the coal industry with job appointments and policy accommodations. The administration, insisting its new rule on mining waste protects the environment, warned this week that the court ruling will mean "severe economic and social hardship for the region," with tens of thousands of jobs at risk along with hundreds of millions in state revenue and profits in related industries. "Mining companies will almost certainly suspend future mining projects in the Appalachian region, lay off existing workers and abandon plans for hiring new ones," Glenda E. Owens, deputy director of the United States Department of Interior for surface mining, cautioned this week in urging Judge Haden to stay his order pending an appeal. The judge is not expected to rule on the stay until next month.

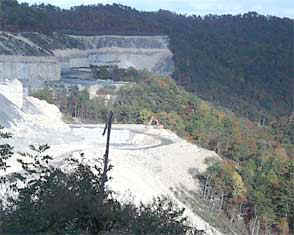

"That's a red herring," said Joe Lovett, director of the Appalachian Center for the Economy and the Environment, one of the litigants suing the corps of engineers. Mr. Lovett said the ruling, if upheld, would protect communities, streams and hardwood forests from destruction and encourage a more balanced economy in lumbering and better controlled underground and strip mining. Judge Haden has been over this legal terrain before. In 1999, he ruled that state agencies had failed to enforce federal environmental protection laws affecting mountaintop removal. Under the process, hundreds of square miles of mountains have been leveled and dozens of communities have been bought out. Judge Haden's decision in that first suit was overturned on appeal a year ago. Without ruling on the merits of the complaint, a panel of the appeals court found that West Virginia had constitutional immunity against the lawsuit. It was filed by a resident who had held out against a buyout when his neighbors abandoned Pigeon Roost Hollow in Blair, W.Va., as waste descended. The new, broader lawsuit was filed against the federal government by community and environmental groups in a four-state coal region of Appalachia. Challenging a mine waste permit last year on the West Virginia-Kentucky border, the groups, operating as Kentuckians for the Commonwealth, charged that the Army Corps of Engineers illegally favored the coal industry by permitting destructive waste disposal in violation of corps regulations that specifically ban such dumping. Judge Haden agreed. The judge shocked the mining industry and environmentalists by reaching beyond the issue of existing regulations to strike down the Bush administration's new rule regarding the dumping of rock and dirt. He said the rule was an effort by federal agencies "to legalize their longstanding illegal regulatory practice." A change that basic, Judge Haden wrote, could only be tried "in the sunlight of open Congressional debate and resolution, not within the murk of administrative after-the-fact ratification of questionable regulatory practices." Industry and government warn of economic ruin from the ruling, with 28,000 miners now at work in the $6.3 billion mining industry in West Virginia and Kentucky, mainly mountaintop removal. The mining industry insists it dumps fill only in seasonal streams, not those running year round, and notes that some companies invest in modified restoration of the shaved mountains. The full damage from the stream dumping is only beginning to emerge, said Mr. Lovett and his co-counsel in the lawsuit, James M. Hecker of Trial Lawyers for Public Justice. They have used the Freedom of Information Act to obtain preliminary reports in a federally ordered consultant's study of environmental effects. Mr. Lovett said the consultants found that the mining industry would be more inconvenienced than devastated by proper application of the Clean Water Act. Coal industry officials, with hundreds of waste applications pending, are counting on another victory on the appeals level to void Judge Haden's latest finding. In making his 1999 decision, the judge not only hiked to Pigeon Roost Hollow to view that site but also flew over the region's many mountaintop removal sites. "The sites stood out among the natural wooded ridges as huge white plateaus," he wrote, "and the valley fills appeared as massive, artificially landscaped stair steps. Tree growth was stunted or nonexistent. The mine sites appear stark and barren and enormously different from the original topography." The judge wondered at all the absent wildlife that "can't be coaxed back." He concluded, "These harms cannot be undone." |

Mountaintop removal mine near Scarlet,

West Virginia. Photo from U.S. Environmental Protection

Agency.

Mountaintop removal mine near Scarlet,

West Virginia. Photo from U.S. Environmental Protection

Agency. Jim Hecker

Jim Hecker Joe

Lovett

Joe

Lovett